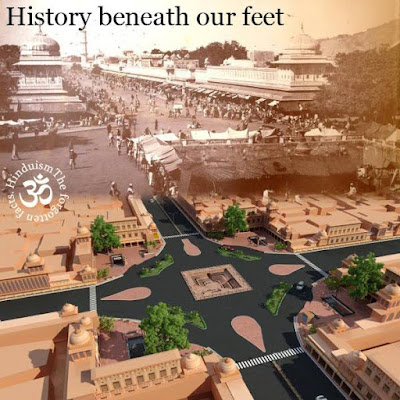

History beneath our feet

When surveys showed two ancient water tanks buried under a planned section of Metro rail in Jaipur, the government worked quickly to preserve and incorporate them into the overall design

For a hundred years, the people of Jaipur had no clue about what lay right beneath their homes. Until last year the Rajasthan government launched its Rs. 3,149 crore Phase I of the Jaipur Metro. As the government made preparations to dismantle two roundabouts in the heart of the city, Choti and Badi Chaupar on the Chandpole-Surajpole stretch, ground surveys indicated that underneath lay buried two nearly 250-year-old bavdis or kunds (tanks) that once brought water to the city centre from the surrounding Aravalli Hills.

The kunds were right in the path of the 12.06 km Mansarovar to Badi Chaupar metro line. The rail portion between Chandpole and Badi Chaupar had been planned as an underground section to protect several heritage monuments in the area. As debates raged about how to proceed after the discovery of the kunds, Rajasthan Chief Minister Vasundhara Raje Scindia asked the Jaipur Metro Rail and the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation officials to alter the design, if required, but to protect the heritage structures at any cost.

The Rajasthan government engaged the services of leading Mumbai-based conservation architect Abha Narain Lambah to map the heritage structures and old buildings. “We convinced people that proven technology, which has been used in fragile areas the world over, would be used and no harm would come to any of the monuments,” says Nihal Chand Goel, CMD, Jaipur Metro Rail Corporation.

“Mr. Goel has a strong connection with Jaipur, and he said there are old photographs of Jaipur taken around this area. We began researching, and found pictures shot by Lala Deen Dayal in the 1890s, which showed the two chaupars,” says Lambah.

Two retired Archaeological Survey of India officials joined Lambah’s team of conservation architects and excavations began in August 2014. “Nobody living knew about these kunds. Around the 1870s, when piped water supply arrived, people were apprehensive and the then ruler of Jaipur had to convince his people that piped water was not bad. The water tanks then slowly became redundant; they were filled with earth and converted into places of beauty and recreation,” says Goel. Later, when Prince Albert painted the city pink, gardens were built around the tanks, which gradually transformed into one of the most congested traffic circles in the old city.

The square kunds had eleven steps and tunnels entering them from four sides, with water bubbling out of beautifully carved marble gaumukhs. “It was a total surprise for us to find the kunds, made of stone masonry, completely intact. We have now mapped and numbered each stone and gaumukh. Everything has been preserved at the government-run Albert Hall until the metro project is complete. We will then restore it all as it was originally,” says Lambah.

According to her team’s research, the tanks brought water from the Aravalli Hills through tunnels into the city centre. The tunnels run along long lengths of Jaipur city and probably connected to the Jal Mahal or Talkatora reservoirs. The teams found them to be well-preserved with arched masonry and lime plaster-lined walls of 500 mm thickness, and large enough for a man to pass through.

Says Lambah, “There is an ancient Persian system of Qanats, an elaborate tunnel network, used for irrigation where there was no surface water. The archaeologists also found material from Bikaner archives that showed that even pitrupaksha rituals were performed in these kunds; like the Banganga tank in Mumbai. Where else will the poor go for water?”

To preserve the tanks, the Jaipur Metro Rail Corporation has altered its design. “We lowered the railway tracks by about one metre and make incidental design changes to accommodate the tanks above the metro stations at Choti and Badi Chaupar,” says Goel. He talks of how people often see development and heritage as two opposing things. “There is no dichotomy; both can co-exist and work with each other. The metro rail rejuvenates the city, and we can also restore a lost chapter of history which becomes a tourist attraction.”

Lambah visited several metro stations, including at Athens and Lisbon, where the developers have used heritage buildings discovered during excavations as part of the railway system. “Lisbon metro station is located in an old heritage building. You come out of the station and you are in a heritage building, with a Starbucks coffee shop, escalators and ticketing,” she says.

The Athens model was chosen for Jaipur. “In Athens, it is open to the sky. It doesn’t rain too much in Jaipur. So we decided to have a sandstone railing as enclosure and keep the station open-air. In Athens, they found 2,000-year-old ruins and they put a glass wall to protect it and made a museum out of it,” she says.

The Rajasthan government plans to set up a museum in the underground station area and use the tunnel heads to let people walk into the tanks. It is also thinking of converting the surface into a pedestrian urban plaza in the evenings, where arts and crafts can be displayed. When completed, this could become a model project for other parts of India on heritage preservation during development.

For a hundred years, the people of Jaipur had no clue about what lay right beneath their homes. Until last year the Rajasthan government launched its Rs. 3,149 crore Phase I of the Jaipur Metro. As the government made preparations to dismantle two roundabouts in the heart of the city, Choti and Badi Chaupar on the Chandpole-Surajpole stretch, ground surveys indicated that underneath lay buried two nearly 250-year-old bavdis or kunds (tanks) that once brought water to the city centre from the surrounding Aravalli Hills.

The kunds were right in the path of the 12.06 km Mansarovar to Badi Chaupar metro line. The rail portion between Chandpole and Badi Chaupar had been planned as an underground section to protect several heritage monuments in the area. As debates raged about how to proceed after the discovery of the kunds, Rajasthan Chief Minister Vasundhara Raje Scindia asked the Jaipur Metro Rail and the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation officials to alter the design, if required, but to protect the heritage structures at any cost.

The Rajasthan government engaged the services of leading Mumbai-based conservation architect Abha Narain Lambah to map the heritage structures and old buildings. “We convinced people that proven technology, which has been used in fragile areas the world over, would be used and no harm would come to any of the monuments,” says Nihal Chand Goel, CMD, Jaipur Metro Rail Corporation.

“Mr. Goel has a strong connection with Jaipur, and he said there are old photographs of Jaipur taken around this area. We began researching, and found pictures shot by Lala Deen Dayal in the 1890s, which showed the two chaupars,” says Lambah.

Two retired Archaeological Survey of India officials joined Lambah’s team of conservation architects and excavations began in August 2014. “Nobody living knew about these kunds. Around the 1870s, when piped water supply arrived, people were apprehensive and the then ruler of Jaipur had to convince his people that piped water was not bad. The water tanks then slowly became redundant; they were filled with earth and converted into places of beauty and recreation,” says Goel. Later, when Prince Albert painted the city pink, gardens were built around the tanks, which gradually transformed into one of the most congested traffic circles in the old city.

The square kunds had eleven steps and tunnels entering them from four sides, with water bubbling out of beautifully carved marble gaumukhs. “It was a total surprise for us to find the kunds, made of stone masonry, completely intact. We have now mapped and numbered each stone and gaumukh. Everything has been preserved at the government-run Albert Hall until the metro project is complete. We will then restore it all as it was originally,” says Lambah.

According to her team’s research, the tanks brought water from the Aravalli Hills through tunnels into the city centre. The tunnels run along long lengths of Jaipur city and probably connected to the Jal Mahal or Talkatora reservoirs. The teams found them to be well-preserved with arched masonry and lime plaster-lined walls of 500 mm thickness, and large enough for a man to pass through.

Says Lambah, “There is an ancient Persian system of Qanats, an elaborate tunnel network, used for irrigation where there was no surface water. The archaeologists also found material from Bikaner archives that showed that even pitrupaksha rituals were performed in these kunds; like the Banganga tank in Mumbai. Where else will the poor go for water?”

To preserve the tanks, the Jaipur Metro Rail Corporation has altered its design. “We lowered the railway tracks by about one metre and make incidental design changes to accommodate the tanks above the metro stations at Choti and Badi Chaupar,” says Goel. He talks of how people often see development and heritage as two opposing things. “There is no dichotomy; both can co-exist and work with each other. The metro rail rejuvenates the city, and we can also restore a lost chapter of history which becomes a tourist attraction.”

Lambah visited several metro stations, including at Athens and Lisbon, where the developers have used heritage buildings discovered during excavations as part of the railway system. “Lisbon metro station is located in an old heritage building. You come out of the station and you are in a heritage building, with a Starbucks coffee shop, escalators and ticketing,” she says.

The Athens model was chosen for Jaipur. “In Athens, it is open to the sky. It doesn’t rain too much in Jaipur. So we decided to have a sandstone railing as enclosure and keep the station open-air. In Athens, they found 2,000-year-old ruins and they put a glass wall to protect it and made a museum out of it,” she says.

The Rajasthan government plans to set up a museum in the underground station area and use the tunnel heads to let people walk into the tanks. It is also thinking of converting the surface into a pedestrian urban plaza in the evenings, where arts and crafts can be displayed. When completed, this could become a model project for other parts of India on heritage preservation during development.

Comments

Post a Comment